Steve took relatively few rosary pictures, and this was the first. We'd brought a "prop" rosary from home, but the priest volunteered to get his personal one to use. It was the first time we'd seen this particular style of penal rosary. The Connemarra marble stones are identical to those in the rosary we brought as a prop. Our rosary was one brought back from a trip to Ireland several years ago, But unlike ours, made from marble beads that are still sharp, hard cubes, this one had the patina of age and use. The stone beads are worn smooth with use, and they slide easily through the fingers, sharp stone made comforting and familiar by countless small touches and voiced prayers.

The one decade rosary is often called the penal rosary. I had assumed it was so named for the common practice of giving a decade of the rosary as a penance after confession. It wasn't until that trip to Ireland that I realized it was named for the Penal Years. In those years, especially under Cromwell, the faith had to be practiced in secret, for fear of arrest or even death. Priests could be executed summarily; mass was often said around "mass rocks" because it was not possible to practice the faith in public in a church. A penal rosary was small enough to hide in one's hand and could be prayed discretely. Unwilling to abandon their faith, the Irish took to the fields for mass, and tucked these small rosaries into their sleeves and pockets.

Priests and laymen alike risked their lives for the faith, among them Blessed Margaret Ball, who sheltered priests and bishops in her home and gave them safe conduct as well as as she could. She died in Dublin prison, sent there by her son the (Protestant) Mayor of Dublin, after he had he dragged through the streets on a wooden hurdle because she was crippled and unable to walk, because she refused to renounce her Catholic faith. All in all, over 260 men and women are known to have died for their beliefs between 1537 and 1714, with no accounting of those who may have perished in anonymity in scattered villages. Bl. Margaret's story gives Christ's admonition that "I come to set a man against his father and a daughter against her mother..." new meaning.

It's hard for modern Americans to imagine a time when praying the rosary could cost one's life, but it could then, and in some places in the world, it can today. Nor is America free of the risks of persecution. One American Bishop has commented that he expects to die in his own bed, expects his successor to die in jail and expects that bishop's successor to die a martyr. Being Christian--being Catholic--is not without its risks, not the safe choice. The admonition to pick up the cross--which led to a criminal's death on Calvary and in a Dublin jail---remains incumbent on us today.

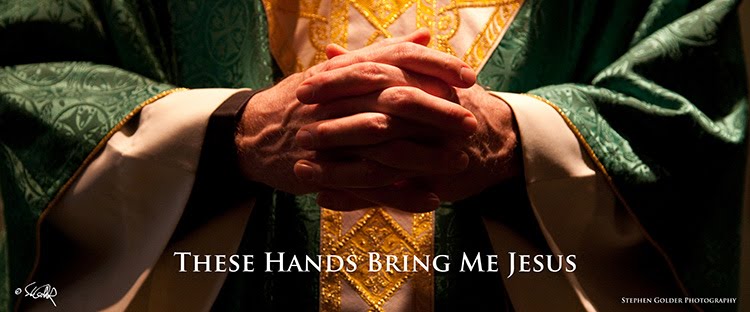

This image was taken in the quiet alcove of a beautiful church in downtown Atlanta, a place full of rich imagery and art, early in November, on the eve of a service in observance of World AIDS Day. The hands convey a sense of calm and confidence. Unlike in the Penal Years, the rosary is in full view, the crucifix and beads dangling outside for anyone to see. But the ring is on the third finger, for the fourth mystery--in the sorrowful mysteries, the Carrying of the Cross. The priest would go on that evening to call the faithful to selfless and loving care of those who are marginalized because of an illness and have themselves been persecuted by fear and ignorance. More than fitting for a stone rosary, fashioned after ones originally made to survive persecution, worn by many decades of prayers, changed but in no way diminished by penal years, then or now. More than fitting for the Catholic faith that survives and flourishes, and the priestly hands that receive it, hold it, protect it and pass it on.