We all have our listening habits. If I have paper and pen in front of me, it's impossible for me to listen attentively and not doodle. Mine is one of the more common listening habits, and one of the less aggravating. In the fifth grade, my son was known to discharge his excess energy in class by shredding anything that came his way. His desk was a mountain of Styrofoam cup shards, dissected Kleenex and minute bits of notebook paper with rubble from the odd writing implement thrown in for good measure.

The physical tics of listening don't mean inattention. Oddly, in fact, they can serve to keep the attention focused, by drawing off the need to move in small and harmless ways, even though to the observer the behavior may look odd or unfocused. I remember hearing my son tell, with great amusement, of the day his teacher, certain he was distracted and not paying attention, asked him a question while he was in the process of disassembling a pencil in his desk. Looking up long enough to engage him, my son answered immediately and completely, then ducked the eraser the teacher shied at his head in utter frustration.

The Catholic habit of holding one thing in mind while doing another is conducive to two-track thinking. If one can hold a rosary, manage the beads, remember the mysteries, say the prayers, intercede and meditate all at once, one is a step ahead of the general population. And it is then possible to go about one's daily business attentive to the job at hand and the fact that God is behind it.

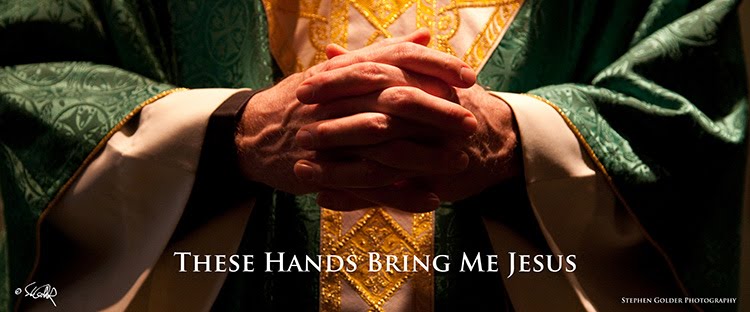

The result is a photograph that invariably gets comments for its strong form and subtle message. The hands are poised and elegant but still convey great strength. They look ready to take on any challenge with Christ as an underpinning, the form in shadow made by the interplay of these hands and the world, the light around them.

As Catholics, it should be our hope that the world sees Christ in all we do, even if only indirectly, and sometimes in the shadows. Like these hands when the Light strikes us, we can show forth a form of Christ, even when doodling on a pad or tearing up paper or twirling a pen. It is possible to make Him present even when we are unaware we are doing it, and the image can be striking to those who see it.

As Catholics, it should be our hope that the world sees Christ in all we do, even if only indirectly, and sometimes in the shadows. Like these hands when the Light strikes us, we can show forth a form of Christ, even when doodling on a pad or tearing up paper or twirling a pen. It is possible to make Him present even when we are unaware we are doing it, and the image can be striking to those who see it.